Written by Dr. Hannes Nel

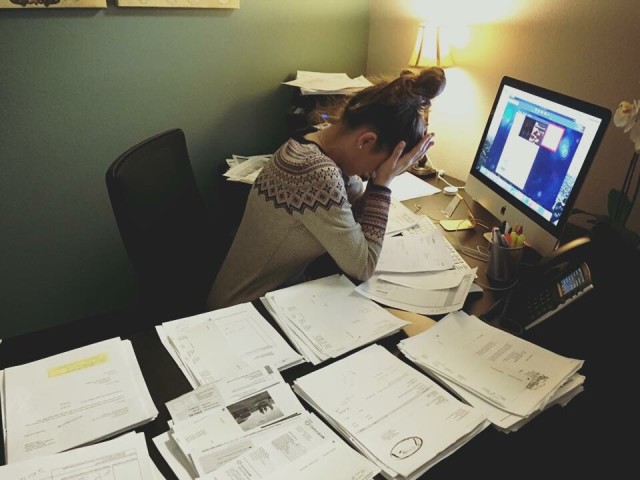

Data collection is at the same time a simple and complex task.

The data that is available on most topics is often vast.

And because there is so much data available, students sometimes spoil their research at this early stage already.

Because they tend to accept any books that they find in the library by searching for key words on computer and in the library referencing system.

And they would accept what people who claim to be experts or people with master’s degrees or Ph. D’s tell them.

It does not matter what the topic of the interviewee’s thesis or dissertation dealt with.

If they have the qualifications their opinions are jam-packed with wisdom and truth.

I discuss applying data collection techniques in this article.

The different research methods provide alternative, though not necessarily mutually exclusive, frameworks for thinking about and planning research projects. In addition to this there are four main data collection methods that can be used with all the main approaches, namely documents, interviews, observation and questionnaires. In this respect four characteristics of documentary evidence are important, namely content, social construction, how recent the documents are, and documents in networks.

The study of content. Documents are used as sources of information when content is studied. Diaries, written life histories and letters can be significant sources of data. In everyday life documents are often records of naturally occurring social events. In addition to this, bureaucratic offices routinely produce rich textual data in the form of medical reports, minutes of meetings, planning documents, memoranda, emails, etc.

When reading the contents of a document, you need to interpret and evaluate the written words. Interpretation will invariably be subjective and different researchers can interpret the same document differently. That is why you need to validate the interpretation of data. This can be done by calling upon many other sources of information, often through a process of triangulation.

The social construction of documents and records. You can also approach research material as data to be drawn and used as facts. The analysis of statistical reports in the form of tables or graphs or both is an example of using records as facts from which we can come to certain conclusions. The production of ‘realities’ from data requires a source, for example statistical reports, rules and technical instructions according to which the data can be analysed and interpreted and grouped. A simple example would be a group of students (the data source) that are grouped into those who are good at athletics, music, mathematics, etc. (according to certain rules for grouping, which can be as simple as asking student what their interests are).

Documents in use. Studying documents that are in use have the advantages that they are recent and mostly provide data in a context that is relevant to the purpose of the research. Such documents are often used to manage projects, for example building plans for a bridge, and as a means of communication between role players in a project.

Documents in networks. Documents often make a big difference to social arrangements and interaction. We have all experienced how a speech can influence the way in which people behave. Documents can also make a difference to the way in which people behave. Marketing, for example, utilise this ability of documents to influence people to establish or increase the demand for a product or service.

Documents can enable us to perform better and safer. Aircraft pilots use documents to check if they are taking off and landing safely. Educators use evaluation check lists to ensure that they offer quality learning. Exam papers are used to check if students meet the requirements for promotion or certification.

Actor-network theory (ANT) supports the idea that documents can function as actors. ANT theory claims that data plays an important role in almost all human activities, including politics, economics, technology, sociology, etc.

Summary

Most researchers use reading documents, interviews, observation and questionnaires to collect data for research.

All data that we collect must be validated.

Documents are mostly used to obtain and study context.

Records can be used as facts from which conclusions can be gathered.

Documents that are still in use provide recent data in a context that is relevant to the purpose of the research.

Documents can influence people’s behaviour and they can enable people to perform better and safer.

Data plays an important role in most human activities.

Interviews, observation and questionnaires deserve special attention.

Therefore, I will discuss them in a series of videos dedicated to each separately.

Close

I hope that, having watched this video, you at least realise that you need to plan and execute data collection for research with great care.

You must plan your data collection carefully.

You must know what you are looking for.

You must have a good reason or reasons why you accept every data source that you use in your thesis or dissertation.

You must know what you are hoping to achieve with every piece of data that you use.

False or irrelevant data can do serious damage to your research.

Don’t even accept what I share in my videos without corroborating my advice.