Written by Dr. Hannes Nel

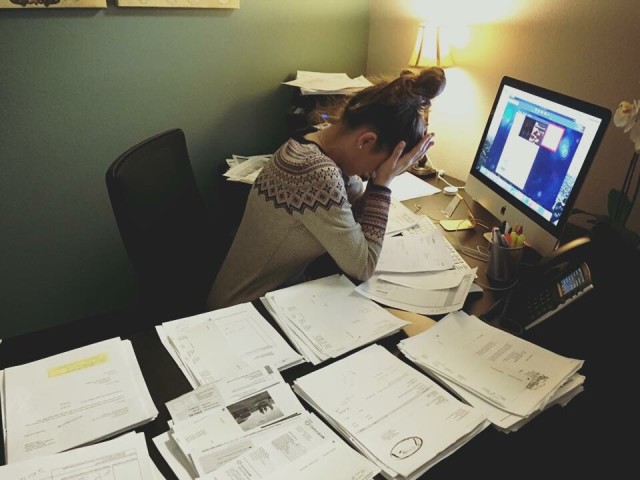

This is the most exciting part of academic research.

Collecting data is an adventure.

It is an opportunity for you to discover things that you never knew or saw before.

The more you set your imagination and creative spirit free, the more original will your research findings be.

And this applies to natural scientists making use of quantitative research approaches as well.

All the data collection methods that I will discuss in the next three videos can also be used as quantitative methods.

It all depends on your imagination and creativity.

I discuss qualitative data collection methods, that can also be used in quantitative research, in this article.

Qualitative research means any type of research that produces findings not arrived at by statistical procedures or other means of quantification. It, therefore, implies qualitative data collection methods. Qualitative techniques collect data primarily in the form of words rather than numbers. The study provides a detailed narrative description, analysis, and interpretation of phenomena. Most interactive qualitative researchers employ several techniques in a study but usually select one as the central method.

To some extent participant observation, observation from the outside and interviewing are part of all interactive research. Other methods are used to supplement or to increase the credibility of the findings. Non-interactive research primarily depends on documents. Qualitative techniques provide verbal descriptions to portray the richness and complexity of events that occur in natural settings from the participants’ perspectives. Once collected, the data are analysed inductively to generate findings. The following are examples of qualitative data collection methods.

1. Artefacts.

2. Graphics and drawings.

3. Interviewing.

4. Observation.

5. Online data sources.

6. Written documents.

Artefacts. Artefacts are material objects and symbols of a current or past event, group, person, or organisation. These objects are tangible entities that reveal social processes, meanings, and values. Examples of symbols are logos and mascots of school teams; some examples of objects are diplomas, award plaques, and student products such as art work, papers, posters, models, etc. The meaning assigned to an artefact and the social processes that produced the artefact are often more important than the artefact itself.

Graphics and drawings. Graphics include any kind of visual data. Researchers tend not to use visual data to the full in qualitative research. Participants in the research can all be encouraged to collect and generate visual data. However, it is you, the researcher, who should use your imagination to illustrate data visually. Visual aids such as diagrams and photos are two dimensional and can be used with good effect. However, in some instances three dimensional visual artefacts, such as models, can also be used. Electronics offer good opportunities to collect and generate visual data, including human-computer interaction.

Visual representations. Not only can you use visual representations to communicate your research data in a report, you can also gather substantial data and obtain comprehension by consulting such representations. Visual representations can be figures, matrices, integrative diagrams, flow charts, graphs, and many more.

As clear as visual representations can be, so can they also mislead you to come to false interpretations and conclusions. It is not always easy to illustrate concepts graphically, with the result that such representations should as far as possible be augmented with clarifying narratives.

Visual data collection and the generation of visual material can include visual material generated by you or other participants in the research and visual material obtained from other sources. Both categories can include photographs, paintings, illustrations, models, clipart, demonstrations and many more.

Visual material can be used to invite responses from readers, to summarise, explain, inform, demonstrate, simplify or add to text or to illustrate systems, processes, etc. An important trend in the use of visual material is what is popularly called ‘participatory’ approaches. Especially electronic devices, such as desk top computers, cell phones, iPads, etc. enable you to capture discussions, demonstrations, presentations, events, and other images which can be used as sources of data or as additional information supporting a research report.

Visual material can, of course, also be the subject of investigation, for example the effect of erosion on farmland, student riots at universities, the daily routine in a correctional facility, oral presentations by lecturers, and many more. Simple observation can offer a way to answer diverse questions about the topic of the research. Video recordings are mostly used for this purpose. Electronic material, however, changes so rapidly that even the term ‘video recording’ is regarded as archaic by some. Videos are no longer used – even CDs are already outdated. People now record moving images on their cell phones, desktop computers, tablets, I Pads, etc. Chances are good that even more modern devices and processes might be in vogue by the time this article is published. Even so, the term ‘video’ seems to be still in use when referring to any recording of moving objects, including people.

Video recordings. Video can be used with good effect to capture and analyse action and interaction. A substantial range of insights and findings have been captured concerning the social organisation of activities within a broad range of everyday environments including the workplace, the home and more public settings such as universities, sport fields, classrooms, etc. In different ways, these studies have built on and developed the rich and diverse range of research concerned with language use and speech that arose over the last three decades or so, and have powerfully demonstrated the ways in which social actions and activities are accomplished in and through the visible, the material as well as the spoken word.

The growing interest in embodied action and multi-modal communication is reflected in the growing commitment to using video in naturalistic research throughout a range of disciplines, including sociology, organisation studies, applied linguistics, education, management and many more.

Video is well-suited to analyse naturally occurring activities. One of the most important contributions of video-based research has been to improve our understanding of education and training and the ways in which learning is accomplished. Lessons and demonstrations are captured on video, thereby substantially multiplying the number of students who benefit from the lectures and demonstrations. Furthermore, researchers can watch the videos any time they want in their offices or homes, which gives them substantial freedom of movement, which, in turn, renders the research process much more effective and efficient.

The use of graphics to clarify spatial relationships is a powerful source of data that can often be used in visual format to report on events, processes and phenomena. A suitable map of a study area may orient readers better than any narrative description of the area. Maps are especially valuable when a qualitative study focuses on a geographic area, such as a place where a natural disaster occurred, a riot took place, and many more.

Maps. Maps can be used even where the focus of your study is not on a geographic area. For example, maps can be used in studies of immigrant movement, including where they come from, the routes that they follow and where they settle. The three types of maps that are often used in research are situational maps, social world/arena maps and positional maps.

Situational maps show the layout of major human, nonhuman, discursive and other elements in the research situation of inquiry and provoke analysis of relations among them.

Social world/arena maps show the layout of the collective role players, key nonhuman elements and the arena(s) of commitment and discourse within which they are engaged in ongoing negotiations, i.e. the meso level interpretations of a situation.

Positional maps show the layout of the major positions taken and not taken in the data, compared to particular variables in terms of which they may differ, including concern and controversy around issues in the situation of enquiry.

Photographs and reproductions. Photographs can be anything of which one can take a photo that is relevant to your research. It may be a place of interest to your study, an event, an individual, even yourself. Thanks to electronics you can take as many photos as you like and then use only the best and most relevant ones in your research. You can often take photos on the spur of the moment with your cell phone.

Reproductions collected during your fieldwork can be reproductions of photographs, but also of works of art, drawings, artefacts, etc. Photographs are often taken by you while reproductions are mostly the work of other people.

Summary

Qualitative data collection methods imply that the collected data will be processes and analysed without making use of statistics or other numerical procedures.

Both etic and emic observation are used in qualitative data collection.

Findings gained from data collected through observation can be corroborated and supplemented by other methods, for example literature study and interviews.

Collected data are analysed inductively to generate findings.

Artefacts are used to reveal historical or current social processes, meaning and values of events and phenomena.

Graphics include any kind of visual data other than artefacts.

You, as the researcher, can and should create visual data.

Visual data include visual representations, visual recordings, maps, etc.

Visual material can be used for the collection of a vast variety of purposes, for example to summarise, explain, illustrate, etc.

Visual material can also be the subject of investigation.

Video recordings and more recent electronic recordings of movement can be used to capture and analyse action and interaction.

Maps can be used in studies of immigrant movements, historical developments, military operations, the spread or contraction of disease, etc.

Photographs can facilitate the research on any visual objects, events or phenomena.

Close

I hope you can now already see the exciting and endless opportunities for research that data collection methods offer.

It is all about imagination, innovation and creativity.

This is where you can make your research an adventure full of surprises and fun.

You can even provide your study leader with a thesis or dissertation that will blow them away.

Enjoy your studies.

Thank you.